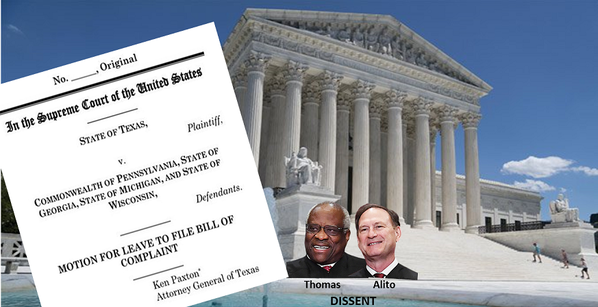

The State of Texas submitted to the United States Supreme Court a petition for leave (permission) to file a Bill of Complaint (lawsuit) against the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and the states of Georgia, Michigan, and Wisconsin. The purpose of the intended lawsuit was to challenge the constitutionality of presidential election procedures in those jurisdictions.

In its lawsuit, Texas alleged outcome-determinative election irregularities in the defendant states and that those irregularities worked an unconstitutional dilution of the votes of Texans.

In its lawsuit, Texas alleged outcome-determinative election irregularities in the defendant states and that those irregularities worked an unconstitutional dilution of the votes of Texans.

The Supreme Court, in a two-paragraph ruling, declined to grant Texas leave to file its lawsuit, stating that Texas did not have standing to sue because it had “not demonstrated a judicially cognizable interest in the manner in which another State conducts its elections.” Justices Alito and Thomas dissented.

When talking about the Supreme Court, it is not uncommon to hear that the Court declined to grant “cert” — certiorari — to a case, that is, that the Court declined to accept a case. This is not surprising as, typically, review in the Supreme Court is sought only after a case has been extensively litigated in the lower federal courts and/or state courts. Cases which attempt to invoke the Court's “appellate jurisdiction” comprise the vast majority of the Supreme Court’s work.

The Supreme Court’s jurisdiction, however, is not limited to appellate cases. It also has original jurisdiction in several other categories of cases, one of which is in cases between two or more states. See, U.S. Const., Art. III, § 2, cl. 2.

When a court exercises original jurisdiction, it fulfills the function of a trial court, not an appellate court. Thus, by definition, when a plaintiff seeks to invoke the original jurisdiction of a court, the plaintiff has not litigated its case in any other court.

Such was the situation in Texas v. Pennsylvania, et. al. Texas sought to invoke the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction — as a trial court, not as an appellate court — to hear its case against Pennsylvania, Georgia, Michigan, and Wisconsin.

Furthermore, because the case was between “two or more states,” no court other than the Supreme Court had original jurisdiction to hear the case. In other words, the Supreme Court was the only court which had jurisdiction to hear the case.

If the Supreme Court had concerns about whether Texas had standing to sue, it could have done what trial courts across the country do on a routine basis: accept the filing of written briefs, hear arguments from the parties on standing and jurisdiction, and then issue a ruling.

By refusing to accept the case, the Supreme Court effectively denied Texas of the right to litigate its case in any court, thus depriving Texas of due process of law. Justices Alito and Thomas appear to have acknowledged this fact in their dissent, which states in relevant part: “we do not have discretion to deny the filing of a bill of complaint in a case which falls within our original jurisdiction.”

The Supreme Court’s jurisdiction, however, is not limited to appellate cases. It also has original jurisdiction in several other categories of cases, one of which is in cases between two or more states. See, U.S. Const., Art. III, § 2, cl. 2.

When a court exercises original jurisdiction, it fulfills the function of a trial court, not an appellate court. Thus, by definition, when a plaintiff seeks to invoke the original jurisdiction of a court, the plaintiff has not litigated its case in any other court.

Such was the situation in Texas v. Pennsylvania, et. al. Texas sought to invoke the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction — as a trial court, not as an appellate court — to hear its case against Pennsylvania, Georgia, Michigan, and Wisconsin.

Furthermore, because the case was between “two or more states,” no court other than the Supreme Court had original jurisdiction to hear the case. In other words, the Supreme Court was the only court which had jurisdiction to hear the case.

If the Supreme Court had concerns about whether Texas had standing to sue, it could have done what trial courts across the country do on a routine basis: accept the filing of written briefs, hear arguments from the parties on standing and jurisdiction, and then issue a ruling.

By refusing to accept the case, the Supreme Court effectively denied Texas of the right to litigate its case in any court, thus depriving Texas of due process of law. Justices Alito and Thomas appear to have acknowledged this fact in their dissent, which states in relevant part: “we do not have discretion to deny the filing of a bill of complaint in a case which falls within our original jurisdiction.”

Disclaimer

The information contained in this publication is provided by Lapin Law Group, P.C., for informational purposes only and shall not constitute legal advice or serve as the basis for the creation of an attorney-client relationship. The laws and interpretation of laws discussed herein may not accurately reflect the law in the reader’s jurisdiction. Do not rely on the information contained in this publication for any purpose. If you have a specific legal question, please consult with an attorney in your jurisdiction who is competent to assist you.

Lapin Law Group, with its principal office in the Dallas-Forth Worth Metroplex, serves all 254 Texas counties.

Lapin Law Group, with its principal office in the Dallas-Forth Worth Metroplex, serves all 254 Texas counties.